I realize that you are too clever to think that Vincenzo Lunardi failed to return from his first hydrogen balloon flight, where I left you at the end of last week’s blog. Clearly, there would have been no reason for a Part Two had this hero checked out in flight. In any event, I want to take a halt before jumping back into what happened to Lunardi, and let you know what I, my wife Cristin, and my son Pablo, got into by reason of our “Lunardi Connection.”

A Twenty-first Century Visit to the Lunardi Society at the Hon. Artillery Company

I was intrigued by the idea of the Hon. Artillery Company. That it still exists, and has six undeveloped acres in the heart of the City of London is, for me, an extraordinary bit of English persistence, despite all odds. Being direct, I decided to make a telephone call to the HAC, and speak to whomever had a handle on its history and Lunardi in particular. And, of course, if Vincenzo Lunardi was indeed a recognized character in the HAC’s history. The telephone operator at the HAC suggested that I speak to the archivist, named Justine Taylor. I was transferred to her line and she picked up the call, saying Justine Taylor here, without the usual voice mail, choice of umpteen options, my leaving a detailed message, and never getting a call back, which is what one expects in dealing with an organization of any size and whatever nationality, whether a dental office to the U.S. Post Office. I was momentarily speechless, which is not generally my suit, but being so used to the frustrating game of answering systems; this was truly a lucky break through.

I introduced myself to Justine Tayler, and said that I was researching all possible leads to learn as much as I could regarding Vicenzo Lunardi, and was initially curious as to whether she had ever heard of him. With a friendly laugh, she said, “Yes, of course As a matter of fact, the HAC has a Lunardi Society amongst its members, and they hold a luncheon on the second Wednesday of every month.” All I could bring myself to say at that moment of instant gratification, was, “Really!”

Ms. Taylor asked why I was so interested in Lunardi; and, I told her about the portrait, and what I knew about him and was interested in anything I didn’t already know. I said also that I had arranged with the Boston Museum of Fine Arts to make a museum quality photographic copy of the painting and could make another for the HAC, should it be interested in having one. She said it was likely that the HAC would be interested, and, as we were speaking, I sent her a digital photo of the portrait. She received it while I was still on the line, and said that she could assure me than the HAC would love to have a copy.

Miss Taylor suggested that when I should be in London, I should attend a monthly luncheon. This telephone conversation occurred in January of that year, and I said that was planning to come coming to London in March. She said that she would speak to the powers that be, and confirm an invitation. I added that my wife and my then fourteen-year old son would be accompanying me, and asked if they could join as well, as I could never leave then out, this being a Spring Break trip. She paused and said that women were never permitted to have a meal in the HAC dining room; it was strictly a men’s organization. Even she, as the archivist of the HAC, had never attended a Lunardi Society or other luncheon. I said that I didn’t want to disrupt HAC traditions, but I couldn’t come as it would be rude of me to leave them behind. Miss Taylor said that she would raise the issue with the head of the Lunardi Society and, to my surprise, she called me back several days later with the good news that all three of us were invited to the March luncheon; and, moreover, she was invited to attend as well of the wives of any members who wanted to come as well. The barrier was broken in a big way.

We arrived at noon at the Armoury House

of the HAC, a handsome eighteenth century honey-colored building sitting on the gorgeous six acre grass playing, in the center of the City of London. We met the charming Justine Taylor and were taken into a room for pre-luncheon cocktails. It was filled with men and several women, to whom we were introduced. It was all very jolly and a fortunate remnant of pre-Big Bang London,

when business lunches were preceded by many rounds of cocktails, a good claret at lunch, brandy after pudding, and everyone going at 4 pm, contrasting strongly with the present day lunch instead of sandwiches and iced tea at a desk or in a conference room at best.I know because my law firm had an office in London at that time. My son was offered a gin and tonic and, when I demurred for him saying that he was 14, the reply was that really didn’t matter. In any event, Pablo chimed in saying that he didn’t take alcohol.

We were the shown the hanging portrait of Lunardi that we had given to the HAC, and then went into the dining room for luncheon. The room was the epitome of an English men’s club, with mellow dark wood paneling, randomly placed tables covered with spanking white table clothes, and portraits of men, mostly in military uniforms, peppering the walls. The table for the Lunardi luncheon was long and set for about 25 people; all of the napkins were embroidered with the motto “Lunardi Society.”

Lunch was a hoot, merry, and merrier as empty glasses of claret were filled and refilled. I was asked to say some words and did. What said I brought laughs, but I can’t remember what those words were. all I know is that I asked for more cheers to Lunardi and the society honoring him. After lunch, the menus with the portrait on their cover were signed with kind words by all present, addressed to me and my wife and son. We were also given as souvenirs the Lunardi society napkins,

used and unused place into a plastic bag for washing. It was good cheer galore. We all promised to keep in touch, and I hope to return this coming April. Lunardi certainly fell into the right berth when his lift-off was accepted by the HAC. I felt happy for him, as I can’t imagine that the HAC membership of his time to have been any different from the good fellow members I met.

Lunardi return to London and Beyond

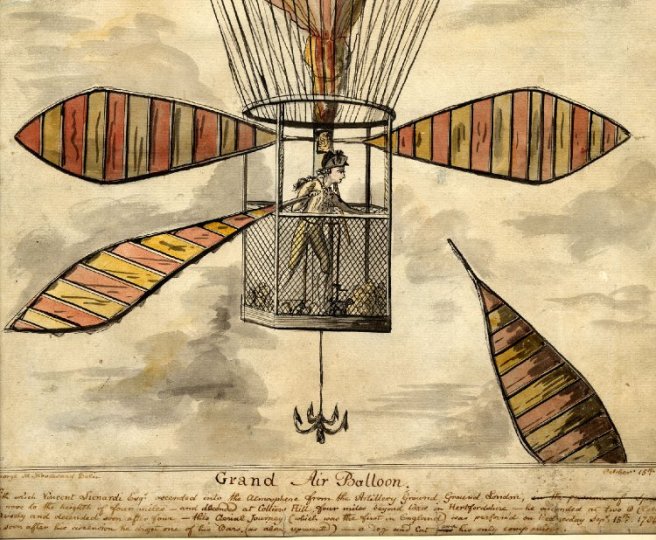

You should know that the best description of Lunardi’s first voyage is contained in a series of letter written by Lunardi that was published as a pamphlet after the returned from that flight, called “An Account of the first aerial voyage in England, in a series of letters, to his guardian, Chevalier Gherado Compagni, by Vincent Lunardi, Esq.” The pamphlet was sold at the exhibition of his new, second balloon when t was exhibited at the Pantheon, another exhibition hall in London. The letters are very readable (other than having to read most “f’s as “s.s), written in excellent, grammatical English, and reveal Lunardi’s charm, intelligence, and humility. Lunardi certainly wrote the letters, but I have no idea of whether an editor was brought to correct grammar and style. But then again, he did study and teach English in Paris prior to going to Naples. Some of the letters are likely to have written in the balloon’s undercarriage during his first balloon voyage.

Lunardi had an easy trip after leaving the HAC field, partly sailing as he notes above large cloud banks as he notes, so common to all of us who have ever flown upon an airplane; but, his experience was beyond the wildest imaginations of all humankind before his time, expect for the very few Continentals who preceded him in their light-than-air craft or perhaps those who crossed the Alps. He mentions the soundlessness of it all, and not knowing how fast or slow his balloon was going, or whether it was ascending or descending, as the balloon traveled without resistance through the atmosphere. This aspect of air travel is not the case on commercial planes, propeller or jet, but was noted by passengers on transatlantic flights of the German Zeppelin,

fortunate not to be on its last flight. Lunardi writes about the perfect round horizon he saw from his height, how well-kept and tidy the green landscapes of England seemed, and how little people and buildings appeared to be below him. He adds that this must have been how the ancients thought of the god Jupiter’s perspective of the earth from his abode in the sky.

Lunardi records that the temperature dropped from 66 degrees Fahrenheit rapidly to 61 degrees and then to 29 degrees, causing “little crystals” to form about the mouth of the balloon. After about an hour in flight, he noticed the ill effect that the cold had upon his cat, and let out some hydrogen gas to land near a small village in Hertfordshire, about x miles from London, to release the cat. Lunardi’s pamphlet of letters has several legal depositions of persons who encountered this landing, as a means of certifying the accuracy of his accounts. One is by a woman named Elizabeth Brett, described as “Spinster’ and “servant to a farmer” who was working in her “master’s brew house” when she heard a loud noise. She went outside and saw a “strange large body” in the air approaching and a man in it.

Once the balloon landed, Lunardi put the cat onto the field where it was picked up by a woman named Mary Butterfield, who was also deposed in London, to confirm her encounter with Lunardi. She had been in the field “raking oats,” and immediately afterward, sold the cat to a “gentleman” standing on the other side of a hedge row; he enlightened Mary Butterfield that the Machine was called an “Air Balloon.”

Lunardi took off again by dropping off more ballast. In a letter to his cousin, Gerardo Compagni, he relates that after a second lift-off, he ate cold chicken, drank some port, and, then, with total sang foid, took a nap. Ultimately, he descended at Standon Green End near the town of Ware, having made a nearly 24 miles voyage that lasted over 2 hours. Lunardi claimed that the balloon sailed upward to the unimaginable height of 4 miles. Although that is unlikely, it is clear that the height he reached was high enough to numb the cat.

When he came close to his second and ultimate landing, Lunardi called from his trumpet to men working in his chosen landing field below to grab the balloon’s ropes and pull him down. But they were too shaken by the sight of a man standing in a basket in mid-air. They shouted to him that would “have nothing to do with one who came from the Devil’s house.” However, a fearless young woman named Elizabeth Brett, also later deposed, realized that the man in the sky was human, took hold of one of the balloon’s dangling ropes, and shouted to the men to join her; they denied her request as well. A man Lunardi identifies as a “gentleman,” named General Smith, and several other gentlemen who followed the balloon on horseback from London as well a “other people from the neighborhood” than the faint-hearted field workers helped to land and secure the balloon. The hydrogen gas was let out to deflate the balloon; and, Lunardi notes that the gas “produced a most offensive stench,

which is said to have affected the atmosphere of the neighborhood.” This, of course, was the downside of landing the safer hydrogen gas balloon, unlike the case of hot-air balloons which simply were filled by hot air that dispersed into the atmosphere.

Lunardi was welcomed back to London in triumph; he writes that:

“No voyager from the most interesting and extensive discoveries; no conqueror from the most important victories, was ever …welcomed with greater joy.”

Perhaps, the foregoing description of his triumph is bit of exuberant hyperbole, but the returning Lunardi truly enjoyed veritable twenty-first century style “pop” status, reaping both the financial and social rewards that such celebrity can bring. What surprised him greatly was that the plates, knives, and forks that he used for eating during his flight as well as an empty bottle of port that he dropped from the balloon as supplementary ballast to gain lift became collectors’ items. He wrote to his guardian Compagni:

“The interest which the spectators took in my voyage was so great, that the things I threw down were divided and preserved, as our people (the Italians) would relics of the most celebrated saint.”

England was enchanted by the idea of balloon flying, as well as with Lunardi. He was made an honorary member of the prestigious Honorable Artillery Company by the support of Prince of Wales, which allowed him to don the stylish red and white uniform of that group shown that he wears in the Portrait. The Prince introduced Lunardi personally to his father, King George the Third. In fact, the four figures that are shown in the mid-right level of the Portrait are the King and Queen Charlotte seated in front of the Prince of Wales and possibly his wife who stand behind them.It would seem possible that the jumping dog in the portrait might have been the same dog that Lunardi brought with him on the first balloon flight.

A ladies’ bonnet shaped like a balloon,

2 feet high, was designed to mark the flight as well as Lunardi skirts decorated with balloon images as well as commemorative plates and other inexpensive pottery items. Georgianna, Duchess of Devonshire, who invited him to a dinner at Devonshire House, her London residence. Lunardi responded to the Duchess’ courtesy by wearing a suit in the color she developed called “Devonshire Brown.”

Colors introduced by important women of the late 18th century on clothing were immediately worn by the “fashionistas” of the age. Another example of this phenomenon is the color “Caca Dauphin” created by Queen Marie Antoinette, also a friend of the Duchess, after the birth of her first son to commemorate his stool.

Richard Gillow who inherited and further carried on the eponymous furniture company, still functioning, become acquainted

with Lunardi in order to encourage and assist him in making a hot air balloon flight in the country of Lancaster where Gillow lived and had his factory. In conjunction with Lunardi, Gillow developed a design for a “balloon-backed” chair which became and remains a very successful model.

Following his success in 1784, Lunardi ordered a new balloon in 1785 with the British Stars and Bars emblazoned upon in vivid red and blues. This was exhibited at the Pantheon, another public hall,

to create excitement for a second lift-off, also to occur at the HAC field. Lunardi planned to have three aeronauts in the carriage, including him, George Biggin who lost out on the first run, and also an actress friend of Lunardi called Letitia Sage, described as a Junoesque beauty, to gin up public interest.

At the awaited hour of lift off, all three entered the carriage, the balloon wouldn’t rise. Madame Sage confessed that she seriously underestimated her weight, which turned out to be over 200 pounds. Lunardi gentlemanly agreed to leave the carriage so Biggin should not miss out a second time; and; Mrs. Sage’s involvement was essential to maintain the gate-paying public’s continued excitement about a second lift-off. Once Lunardi left the carriage, the balloon easily into the air. However, as the balloon was rising, the portal to the carriage opened, not a serious problem but the crowd below were worried. Mrs. Sage gamely got down her hands and knees to tighten the lacings. This titillated prurient-minded members of the spectator who chose to think that she and Biggin were in flagrante delicto,

creating even more approval for the first female aeronaut; and, they roared their delight. The couple’s flight was otherwise uneventful and their balloon came to earth easily. Lunardi’s reputation was further buttressed after the second voyage for his gentlemanly willingness not to exclude Biggin for the second time and his choice of the fetching Mr.Sage as co-pilot. Mrs, Sage commented in the relacing event in her book on ballooning,speaking i n third person, for whatever its worth:

creating even more approval for the first female aeronaut; and, they roared their delight. The couple’s flight was otherwise uneventful and their balloon came to earth easily. Lunardi’s reputation was further buttressed after the second voyage for his gentlemanly willingness not to exclude Biggin for the second time and his choice of the fetching Mr.Sage as co-pilot. Mrs, Sage commented in the relacing event in her book on ballooning,speaking i n third person, for whatever its worth:

“Mrs, Sage didn’t lose her head, despite the swaying of the basket during the ascent.She simply knelt down and re-fastend the curtain securely.”

Lunardi made several more flights in England and then in Scotland, but the urban population became accustomed to the sight of men and women in the sky, and lost their initial passion for ballooning. Lunardi tried to devise more purposeful inventions to reignite excitement, but he became viewed simply a showman. His ultimate fall from grace in the United Kingdom occurred when a young helper got entangled in the balloon ropes, was hoisted in the air, and then fell 100 feet to his death at the hands of his horrified parents. Lunardi was heartbroken by this dreadful accident; and, after a period of self-imposed inactivity, he moved to the Continent and had a string of mixed successes and some misfortunes in France and then home to Lucca. There, in his native town, he organized a lift-off before a very large audience, but the balloon had multiple false starts, rising a few feet and then falling back to the ground. When it was finally ready to go, after nearly 10 hours of delay, Lunardi tripped on entering into the balloon carriage; and, it sailed unmanned into the sky. He was humiliated and shortly after hiding from shame in Lucca, moved on to Rome, where he would encounter his greatest defeat.

Unlike Lucca, which was a tranquil boondock, Rome was a sophisticated city whose populace was well aware that Lunardi had conquered the hearts and mind of England, not a mean feat for an Italian given the English xenophobic reputation. Lunardi scheduled a lift off in an amphitheater that was brimming with Roman. All seemed very propitious for a successful lift-off and flight; the kind weather was and his equipment and crew were top quality. As fate would have it, a man, described in Leslie Gardiner’s book, “Man in the Clouds,” as a malicious little hunchback named Carlo Lucangeli, kept taunting Lunardi, and became even more strident as he realized the possibility of Lunardi’s successful lift-off. He kicked the undercarriage, which was Lunardi’s straw. He picked up his tormenter, turned him upside down, tossed him into the carriage, and cut the ropes. The balloon ascended gracefully into the sky and made a smooth fourteen-mile journey, the longest yet achieved in Italy. Moreover, Lucangeli landed the balloon safely; how he did that a mystery, but had the last laugh on poor Lunardi. The following quip was pasted after the Lucangeli’s flight on Rome’s famous “talking statute,” Pasquino.

“Lunardi remained on the ground like a clod,

While old Carlo went up for an audience with God.”

You probably know this if you have spent much time in Rome; however, for those who haven’t, Pasquino was not an individual, but the name given to an ancient fragmented torso dating from before the Common Era, which was and still exists nearby the Piazza Navona. By tradition, anonymous comments, usually satirical and directed at Rome’s high repressive papal government (and in the Papal States as well) or prominent individuals such as Lunardi, were stuck into the base of the statute. Satirical quips are still called “pasquinades.”

Pasquino’s wisecrack spread like wildfire throughout Rome. Poor Lunardi left Rome, as the expression goes, with his tail between his legs and returned to Naples. The Kingdom of the Two Siciles was still a backwater, albeit on the edge of revolt and/or conquest by Napoleon. Ferdinand IV and his Austrian Queen, always receptive to diversion for their sake and that of their restive population in the ancient Roman style of bread and games to quell discontent, were aware of Lunardi’s success in London via Prince Caramanico; and, when welcoming him back to Naples, even claimed that they remembered him from his earlier sojourn in Naples, which undoubtedly was a pleasing exaggeration. No one had to date made a balloon fight in southern Italy; and, the populace was therefore less blasé than the crowds in the north.

Lunardi was given a sinecure, a residence at the Palace of Capidimonte for himself, and funds for the building of a balloon, as well as a staff to tend to his needs, personal and balloon making. Lunardi finally reached a secure stage in his life where he was both respected and enjoying the trappings of his celebrity. Unfortunately, as Ferdinad had nothing else of note to say to his father in Madrid, he boasted of housing the famous balloonist at his court, to keep the Royal Family amused and his subjects diverted from nefarious conduct. This struck a chord to Charles, as he had a need for a Lunardi type at his court and in his nation, Spain being restive as most of Europe after the French Revolution.

Finally, Lunardi was persuaded to go to Madrid, which he did in 1793, as certainly it was a more significant world stage than eternally frivolous Naples. He achieved some mixed success in the Iberian Peninsula, but nothing compared to his splash in London. Lunardi went to Portugal for ballooning, but got caught up in Portugal’s war with Spain, at least the extent of wearing a Portuguese military uniform and unlikely was involved in any military action. “Man in the Clouds” states that in or about 1804, Lunardi went back to London for the first time. Leslie Gardner quotes “an announcement” in the London “Morning Post” that “Lunardi the aeronaut is arrived in London, and mediates an aerial ascent in the course of the ensuing month,” This ascent never occurred. However, Lunardi’s “second coming” in London is important to the authorship of the Portrait, a discussion that follows.

After that trip to London, there is no record I have found that traces Lunardi’s steps after he left London. The next and final notice regarding Lunardi appeared in the English publication, “Gentlemen’s Magazine” on July 31, 1806, to the effect that “Mr. Vincent Lunardi, the celebrated aeronaut” died of a decline in the convent of Barbadinos at Lisbon. We know that guardian Gherdo Compagni died more or less before Lunardo returned to Italy; and, that one of his sisters married an elderly noblemen possibly from Sicily, and the other had disappeared from any record. Also, it appears that Lunardi left no wife or heirs. Truly, this was a sad instance of sic transit gloria. But then again no one can contest that Lunardi lived life to the fullest; if not uniformly successful, he always came back for another round.

The Passage of the Lunardi Portriat

The history of the Lunardi Portrait is clear from 1899 to date, with a few minor a few gaps. However, from the time that it was painted until it was purchased 1899 by Agnew’s, a major art dealer in London, then and now, it’s history is a “black hole.”

The painting was purchased from Agnew’s in 1903 by the 4th Baron Ribblesdale. This consummate English lord is the subject of a full-length, life size portrait by John Singer Sargeant,

which is now in the National Portrait Gallery. Ribblesdale is shown wearing an elegant and high glamour hunting costume, topped off by a high and glossy black silk hat. Even King Edward the Seventh, Queen Victoria’s son, who was considered by many Englishmen of his day to be a “German” due to his Hanoverian and Saxe-Coburg antecedents, dubbed Ribblesdale the “Ancestor,”

as representing the quintessence of the grandest English lord descended from the Norman conquerors. Ribblesdale remarried in 1919 and built a large house on Green Street in London which was furnished, amongst other things, with the Lunardi portrait and one other Zoffany. His new wife was an American beauty named Ava Willing,

but she was also Mrs. John Jacob Astor IV,

the ex-wife of the Astor who abided by the “women and children first” rule and went down willingly with the Titanic. Mrs. Astor had been divorced from her Astor husband prior to his demise, but was mother to Astor’s son Vincent, who became the richest person in the world in 1912 upon his father’s death. The new Lady Ribblesdale was much admired in British society but never attained notoriety for maternal instincts. She found little Vincent irritating and a burden on her time, especially since he was inexplicably attached to her. Her means of coping with his maternal “addiction” was to lock the boy in her closet, leaving him there until someone else stumbled upon him, which was at least once 8 hours later. Is it any wonder that the little rich boy evolved in a manic depressive with a high predisposition to aIcohol. Vincent Astor married one woman after another, all of whom were quickly willing to leave the unhappy, albeit richest man in the world. As for his third wife, he found a woman willing and able to put up with him, a young widow with young children who upon being widowed again became a beacon of sanity, charity, and glamor as the surviving Mrs. Vincent Astor, who was sadly fleeced by her own son, now in prison, in her foggy dotage.

After Ribblesdale, the Lunardi Portrait was owned by Knoedler, a New York dealer in old and no-so-old masters, a firm now in disrepute from recent sales of allegedly fake Rothkos. I don’t how Knoedler got hold of the painting, but sold it to a very rich American family named Crane from Chicago. Mr. Crane owned a large company that made residential and commercial plumbing under

an eponymous name and still is functioning. In 1900, he bought a glorious property to serve as a summer residence consisting of 3,500 acres overlooking the Atlantic Ocean on three sides in Ipswich, Massachusetts. In 1911, he built a large and, from photographs, what seemed to be a seemingly charming Italianate villa/mansion of the Newport variety to crown the highest peak of the property overlooking a mile long rolling tree-lined allee leading to the ocean, similar to one at the Peterhof palace in Puskin, formerly TsarRussia. The landscape was designed by Frederick Law Olstead. Mrs. Crane, for reasons not clear, detested the house from the time it was built and made that evident to her feckless husband. As a means of mollifying her unhappiness and hoping that in time she would come to like the house, he promised that he would tear it down and built a new house of her choosing if in ten years time she had not come around to appreciating the house. In 10 years to the hour and day, Mrs. Crane reminded Mr. Crane of his promise and her unrelenting loathing of the existing house.

The existing Crane house is on the left side, the grand allee to the ocean is shown on the upper right side, and the demolished Italianate house is on the bottom right

Mr. Crane complied, and one can speculate that he viewed this submissive course of action to be less expensive than a divorce with what also from photographs and portraits looks to have been a very beautiful woman, but very “special”, as that adjective is used derogatorily in Spanish.

The villa was demolished and on its site the Cranes engaged David Adler an amateur architect, but extremely amateur, as well as a very accomplished interior designer from Chicago to design and built a large and very tasteful, albeit restrained, Jacobean-style brick house, differing widely from its exuberant Italianate predecessor. Presumably, Mrs. Crane was satisfied with her new house, and perhaps more so that “her will was done.”

The Crane family gave up Castle Hill as a personal residence in 1949, after Mrs. Crane, then a widow, died. The house and property was given to the Trustees of the Reservations, a private, not-for profit trust established in 1877, to hold and preserve historic houses, farms, and beautiful beaches and landscapes in Massachusetts, now over 100 in number. Curiously, this organization provided the structural framework for the English National Trust set up in the early 1940’s, to takeover great English houses after World War II whose owners could no longer maintain them, being taxed to absurd extremes during life and then again upon death by the Socialist Government of that era that was opposed to private wealth and diffident, even hostile to its vestiges that the country houses represented. This is a rare instance of the English looking across the Atlantic to find a suitable means of preserving their history. Most of the furnishings of the house, including the Lunardi portrait,

were sold at Parke Bernet, the American auction house that was bought by Sotheby’s, at an on site auction. It is likely that Knoedler bought the painting at the Crane auction and sold it to Walter Chrysler, Jr.

From the time of Agnew’s ownership until 1989, the Lunardi portrait was considered to be an authentic Zoffany. It was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1919 as a Zoffany; and, there was an authoritative statement in Victoria Manner’s

“definitive” book on Zoffany published in 1920 that it was painted by Zoffany, with the reasons for that judgement. However, my initial research after I bought the painting suggested it was unlikely that Zoffany could have painted the portrait, because Lunardi’s first balloon occurred in September 1784 and Zoffany had left England for India in 1783, returning to the UK only after Lunardi had left for the Continent in 1789. I obtained a copy of a Sotheby’s 1989 for the sale of Walter Chrysler’s old master collection. There, for the first time, the portrait is attributed to the painter John Francis Rigaud, with no “by your leave” as to its earlier but Zoffany attribution.

I spoke to the painting person at Sotheby’s who was familiar with the sale and said Sotheby’s also realized the likelihood that Zoffany didn’t paint the portrait as he, the painter, was not present in London while Lunardi was there. He added that the Rigaud attribution was based solely on its stylistic similarities without any hard information linking this particular painting it to Rigaud. Richard Crossway and Bartolozzi did do portraits of Lunardi, and Rigaud did do a painting on copper of Lunardi with George Biggin

and Letitia Sage in a balloon. I personally never found the attribution to Rigaud very satisfactory on stylistic grounds. I also spoke to a curator of a recent Zoffany show, who virtually hung up on me when I asked if he had any relevant information about my “Zoffany/Lunardi. He said before finishing the conversation that “everyone knows that the two men weren’t in London at the same time, and added gratuitously that no one currently paid attention to Victoria Manners. However, until yesterday, any realistic attribution of the portrait to Zoffany seemed at best unlikely as the two clearly weren’t in the United Kingdom at the same time. I say “until yesterday” because I finished yesterday reading Leslie Gardner’s biography of Lunardi, Man in the Clouds and saw the notice in the London Morning Post, announcing Lunardi’s arrival in London in 1804, a year in which Zoffany was without doubt in London. Perhaps, Lunardi commissioned the portrait himself for old times’ sake, that the portrait didn’t remain in the United Kingdom, but accompanied back to Portugal. Lacking heirs, who knows where it might have been after Lunardi died, until it was bought by whomever or whatever in turn sold it to Agnew’s. I had spoken to the archivist at Agnew’s who told me that some old documents inidicate that Agnew’s bought the painting from someone or some business called “DRYERES.” She said that she couldn’t find any thing which could identify Dryeres as an auction house or dealer or otherwise. I haven’t been able to find anything on Dryeres as well but I have to search outside of the United Kingdom. Perhaps, one or more or my readers can help in this quest.

Next week our fourth issue will begin to explore the incredible life of

Brook Watson . The second of three dead white men whom you should know.

Brook Watson . The second of three dead white men whom you should know.